Close your eyes. Imagine you are walking through an area of pristine forest. The air is completely pure and you can taste the freshness with every breath. No diesel particulates, no fumes, no dirty urban smells. The light casting a dappled pattern on the forest floor is also free from any human interference. There are no streetlights nearby and there isn’t a glow on the horizon from the combined light emissions of a thousand homes. The only sounds are the interactions of the natural world; wind passing through the branches of the ancient oak trees that surround you, water burbling over rocks in the river and birds calling to one another in the never-ending quest to find a mate. You pause and bend down to drink from the river and find that the water is also free of any unwanted additions. It’s clear and tastes sweet. There is no agricultural run off to sour it, there are no sewage overspills upriver and no scum floats on the surface. In fact the only movement in the water is the darting of tiny fish as they travel from their spawning grounds in the gravelly sediment of the upper reaches.

As you peer into the forest more intently you recognise that the full age spectrum of trees are growing all around you. This forest is predominantly made up of oak trees, a creature that can live for up to a thousand years, and you can see tiny saplings in the first burst of life growing in the shade of giant nurturing old mother trees who are likely entering their sixth or seventh century. In between there are excitable juvenile trees that crest at head height, proud mature oaks producing an abundance of acorns and weary veterans whose roots intertwine with the mycelial fungal network that creates a mat beneath your feet that your toes sink into. They all jostle for space amongst a neighbourly riot of red berried rowan, catkin draped hazel, pale barked holly and thirsty springy willow. The rocks are covered in sphagnum moss, so soft and spongy that they would make perfect bedding if they weren’t so sodden. The bases of the trees are surrounded by a cacophony of brambles, ferns, bilberry and toadstools while in the canopy a graceful garland of spearmint lichen coats the branches and hangs down like living stalactites all the way until their outstretched fingers gently stroke the mycorrhizal floor.

“Humans are the most influential ecosystem engineer in temperate rainforest zones and we are now waking up to how precious they are and how we can protect and expand them for future generations.”

Suddenly you notice movement around you and see a flash of red high above as a red squirrel flings itself from one dwindling branch to another with a lightning fast pine marten in close pursuit. The sonorous sawing sound of teeth on wood tells you that a family of beavers is improving the river system nearby and flattened undergrowth within a small rock cavity gives away wild cats who are denning in the area. A woodcock rises in a rush from beneath your feet, darting between the branches as it searches for the open sky while a white stork flaps by lazily keeping a keen eye on the river and paying no attention to the osprey circling higher still in the ecstatic midst of a spiraling thermal. The crack of a snapped twig draws you to a roe deer furtively darting from hiding place to hiding place, moving quickly to avoid the occasional lynx that it knows hunt this valley and, further away, a red deer stag in rut bellows as he marks his territory in spite of any wandering wolves who might be on the prowl.

This is a celtic temperate rainforest. The British Isles were once wealthy in this pure and ancient habitat all along our western coastline from Stornoway on the Isle of Lewis to Lands End in Cornwall. Nearly all of it is gone; cut down over the last thousand years to make way for marginal farmland where little is grazed but sheep, a non-native herbivore that will eat anything it can get its lips around and which currently requires subsidies of up to 90% of the cost of farming them just to help farmers make ends meet. The slivers and pockets of rainforest that remain are all slowly dying. Few young oaks can survive in a landscape where armies of deer roam unchecked by their natural predators and who devour anything with the temerity to poke its head through the soil. Non-native animals such as grey squirrels and rabbits run amok, stripping bark and harvesting acorns for their winter feasts. Inedible flora like rhododendron and beech begin to take hold like inkblots spreading over pristine vellum as generations of oak, hazel and rowan give way to the unstoppable advance of trees that plant collectors and foresters have introduced over the evolutionary heartbeat that is the late Anthropocene. At this rate in 100 years there will truly be no rainforest left on the European Atlantic seaboard. A tragedy is slowly playing out before our eyes and most of us aren’t even aware of what beauty is being lost.

Fortunately the fight is not over yet. Humans are the most influential ecosystem engineer in temperate rainforest zones and we are now waking up to how precious they are and how we can protect and expand them for future generations. The quest to end our disconnect with nature is gathering steam and temperate rainforests are the finest habitat in the British Isles for carbon sequestration, ecosystem services and mental health and wellbeing. They are the jewel in our national crown and the time is upon us to grasp them by the root and roll their healing embrace back across our western uplands before they irreversibly fade into the night.

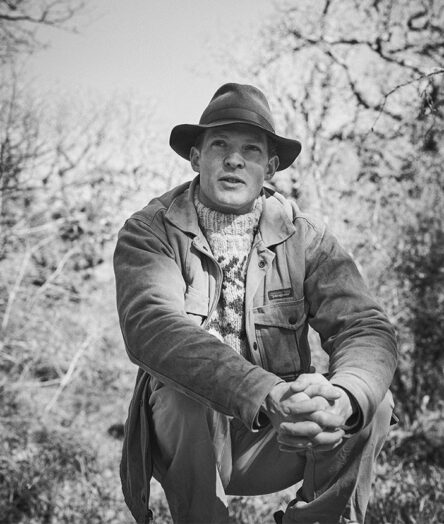

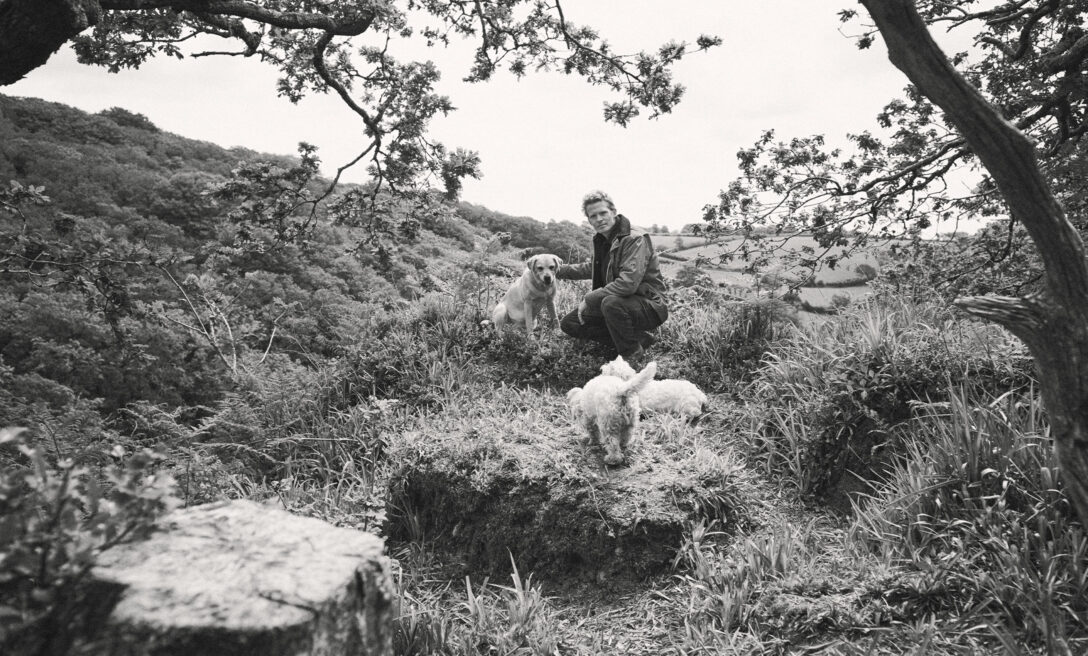

At Cabilla Cornwall we have the huge honour of stewarding 100 acres of temperate rainforest in our valley. We have been working for several years on The Thousand Year Project, our restoration programme to triple the size of this forest and to return all of the species that it is missing. We are now launching The Thousand Year Trust. This will be the first and only charity in the UK with the sole purpose of protecting, promoting and expanding celtic temperate rainforest environments wherever they are found. If you would like to know more about this vital, multi-generational mission then please do get in touch, support our work and come and join the Cabilla family.